This is really about how much exercise is enough.

We can all agree that when it comes to physical activity, some is better than none. But once you start getting active, how much is enough?

Last week on Sunday, I played beach volleyball for 3 hours (180 minutes) and my activity tracker shows I burned 1655 calories. So I took the rest of the week off from exercise, right? (Smirk emoji)

The often-quoted Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that adults get at least 150 minutes per week of “moderate” intensity or 75 minutes of “vigorous” intensity exercise. There are significant problems with these guidelines – both conceptual and physiological.

Hey, I got 180 minutes on Sunday. And at least some of that was vigorous. So I’m done for the week with exercise (and I’ve got an extra 30-minutes banked for the following week), right?

Beach volleyball is something I happily share with my stepdaughter. When you can combine a challenging physical activity you enjoy with people you love, you have reached fitness nirvana…what it really is all about. We’ll be spending Father’s Day evening playing volleyball together.

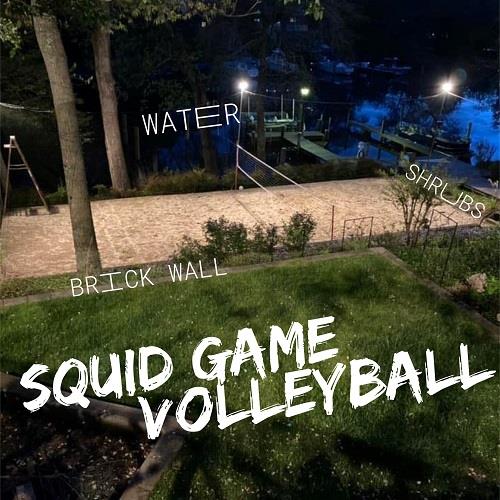

The photos above show the court we have been playing recently. We call it “Squid Game Volleyball.” There is a brick wall defining one side of the court, a drop off into the water on the other side. And at opposite ends lies shrubs. It’s about as unexpected a place for a beach volleyball court as I’ve seen but somehow it works – and no one has been “eliminated” a-la Squid Game (or even injured.)

Now back to the problems with the Physical Activity Guidelines.

Conceptual Problems

Imagine if I told you that you should brush your teeth 14 times per week? Not very helpful. Why are we given weekly recommendations for a daily activity? We perform physical activity on the scale of minutes or hours. In other words, on a daily – not weekly – basis. Weekly guidelines mean we must do math (another thing many people dislike) to figure out if we satisfy them.

Further, our brains often misinterpret guidelines – which are, by design somewhat nebulous and not absolute – as rules. Thus, if we do less than ‘enough’ (erroneously interpreted as 149 minutes or less in a week) our internal ‘pass/fail’ teacher gives us a failing grade and we get down on ourselves, discouraged, and perhaps give up.

The poorly crafted messaging has resulted in people who think 150 minutes in one day is enough and then can enjoy six days off. Obviously, this is not the intention of the guidelines, nor will anyone enhance health or fitness pursuing physical activity once or twice a week and remaining inactive other days.

Breaking down the numbers, 150 minutes a week equals a little more than 21 minutes a day. And this presents another problem when we look at the guidelines through the lens of physiology.

Physiological Problem

150 minutes of walking per week reduces overall mortality rate by 7% compared with being sedentary. Walking twice as long – 42 minutes a day or 300 minutes per week – yields twice the benefit with a 14% reduction in mortality risk. (Greger, 2020) (Samitz, 2011)

Walking less – 8.5 minutes per day (60 minutes per week) – decreases mortality rate about 3%. An hour-long walk each day (360 minutes per week) may reduce mortality by 24%. (Woodcock, 2011)

When it comes to light to moderate physical activity, some is good and more is better. Why is the recommendation only about 20 minutes per day?

Health authorities seem intent on softening the blow of the science on physical activity and health because as a society, we can’t handle the truth. Hunter-gatherer societies walk between 15,000-18,000 steps per day as part of normal levels of physical activity while we fight to fit in 10,000.

Worse, there is not even agreement among major health authorities on physical activity recommendations. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends 30 minutes per day (210 minutes a week), a striking difference from the 150 minutes per week recommended by the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services.

The takeaway: The 150-minutes of moderate exercise recommended in the guidelines are clearly arbitrary and chosen more as a compromise between what the science says and what the public is willing to hear.

This is not to say that since more is better no amount of exercise is enough. Using weekly guidelines for daily activities is inherently flawed and that softening the realities of the science into guidelines around minimal amounts leads many people to treat the minimum amount as if it is the optimum amount and not do one minute more. Regular exercise provides opportunities to move more and more enjoyably which naturally leads to moving more frequently.

Get moving consistently, mix different intensities with different activities, and have more active days than inactive days. Forget tracking weekly minutes of a daily activity. An essential part of doing this successfully involves choosing enjoyable activities rather than forcing yourself to do ones you do not enjoy. That can take time to figure out so stay consistent, patient, and explore what works for you.

Less counting, less tracking, less worrying if you’ve done enough. It’s time we spent less time thinking about whether we’ve done enough and more time moving more often in more enjoyable ways.

References

Greger, Michael. (2020). What Exercise Authorities Don’t Tell You About Optimal Duration https://nutritionfacts.org/2020/07/30/what-exercise-authorities-dont-tell-you-about-optimal-duration/

Samitz, G., Egger, M., & Zwahlen, M. (2011). Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. International journal of epidemiology, 40(5), 1382–1400. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr112

Woodcock, J., Franco, O. H., Orsini, N., & Roberts, I. (2011). Non-vigorous physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq104